The Illuminati, or the lodge that holds power

“I used: Juan Carlos Castillón, “Masters of the Universe: A History of Conspiracy Theories”, 2007; Daniel Pipes, “The Power of Conspiracy: The Influence of Paranoid Thinking on Human History”, 1998.”

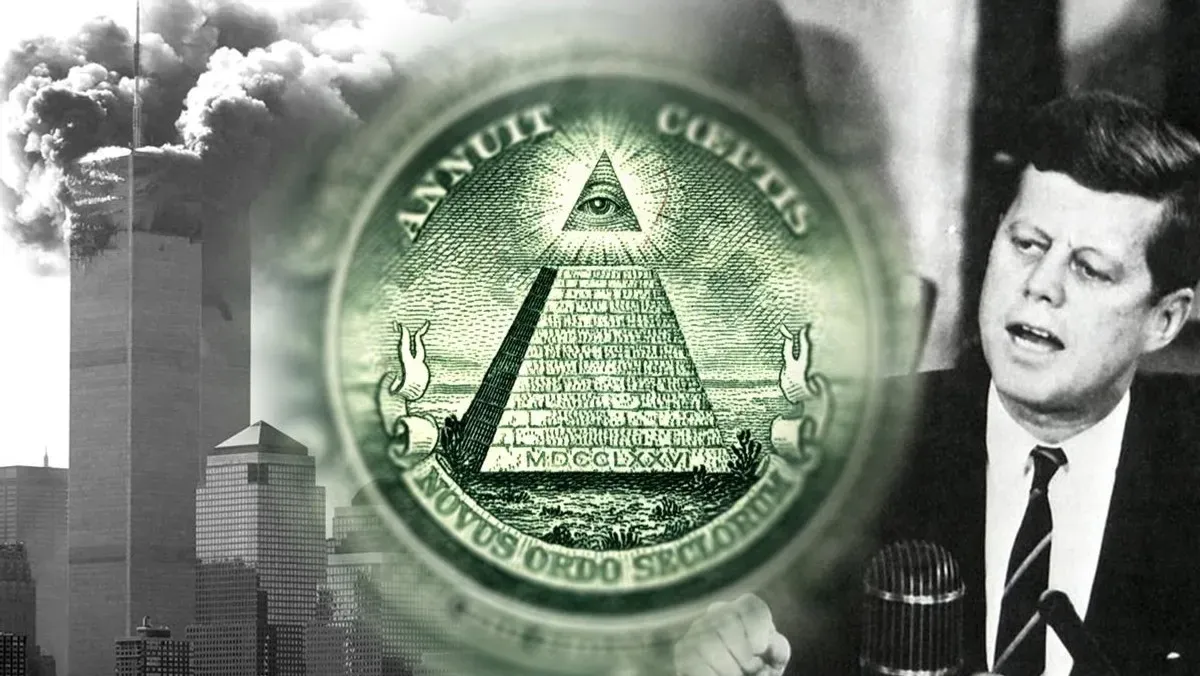

What connects the founding of the United States, the French Revolution, World War II, the assassination of JFK, the death of Princess Diana, and the attack on the World Trade Center? The answer is simple: the Illuminati.

The Illuminati’s goal is to completely subjugate humanity, turning it into a willless mass willingly fulfilling the rulers’ every whim. These rulers appear in numerous incarnations, sometimes representing groups seemingly hostile or at odds with one another.

This cunning camouflage allows them to achieve their criminal goals even more effectively. Freemasons,Nazis, Jesuits, Vatican officials, bankers, top politicians, secret service chiefs, army generals, royal families — daily immersed in show-off conflicts, espousing entirely different value systems — all, without exception, are in reality playing for a single team called the Illuminati.

And although the authentic Illuminati, one of many secret societies that emerged in Western Europe in the 18th century, existed for only a few years, the legend grew to unimaginable proportions.

Unlike the most popular conspiracy theorists today — the American Jordan Maxwell (allegedly the model for Robert Langdon in Dan Brown’s “The Da Vinci Code”) and the British David Icke, who trace the story of the most horrific conspiracy in history to either ancient Egypt or even the Stone Age — historians are surprisingly united on this point. The Illuminati was founded on May 1, 1776, in Bavaria, by Adam Weishaupt, then a 28-year-old professor of canon law at the University of Ingolstadt.

This exceptionally ambitious young man, descended from a family of typical Enlightenment freethinkers, was educated under the stern eye of the Jesuits. He owed his rapidly developing academic career to the extensive acquaintances of his grandfather, Baron Johann Adam von Ickstatt, a rationalist and atheist. After Pope Clement XIV suppressed the Jesuit Order in 1773, Weishaupt assumed the chair of canon law as the first secular professor in history, one who held remarkably progressive and anticlerical views.

It was likely the still very strong Jesuit influence at the university that prompted Weishaupt — endowed with an exceptionally egocentric and rebellious personality — to form an association, which was initially intended to provide a resource in his numerous conflicts with Church representatives. For a while, he sought support from the then-developing Freemasonry, but he quickly concluded that the best solution would be to launch a clandestine operation on his own.

Initially, the Bavarian Illuminati was called the Order of Perfectionists (Bund der Perfektibilisten) and had just five members. After three years of operation, their number increased to fifty-four, and Illuminati branches appeared in four other Bavarian cities. Paradoxically, Weishaupt — a true Jesuit hater — drew heavily on Jesuit models when creating the structure of his association, or rather, on everything their most ardent enemies had written about the Jesuits (about whom the most bizarre stories were told at the time).

Although the ideology of the Illuminati was permeated with 18th-century Enlightenment rationalism, republicanism, opposition to all forms of absolutism and the domination of the Catholic Church, the structure of the association was extremely hierarchical and secretive.

There’s also no doubt that Weishaupt was gripped by a genuine lust for power. In 1777, he joined a Bavarian Masonic lodge, dreaming that in the near future, he and the other members of his society would completely subjugate global Freemasonry. Due to limited financial resources and rather meager strategic planning, this plan, of course, quickly backfired. Despite this, the Illuminati continued to grow, and a turning point in their history came in 1780, when Baron Adolph von Knigge, a wealthy and experienced German Freemason, joined them.

Thanks to his activities — both theoretical, expanding the order’s ideological message, and practical, strengthening their position within the then-aristocratic world — within two years, the Illuminati grew to several hundred members, with representatives in academic and bureaucratic circles. Soon the order’s influence grew so much that a large number of German Freemasons became its members — among them Johann Wolfgang Goethe, the author of “Faust” (the titular hero is said to have been modeled after Weishaupt), and Illuminist lodges were also established in Sweden, Russia, Denmark, Poland, Hungary and Austria.

The desire to dominate Freemasonry, and then to seize world power and fundamentally reshape social reality, ultimately led to the Illuminati’s downfall. German Masons became increasingly distrustful of Weishaupt.

His self-confidence and tendency toward excessive secrecy at one point even seemed suspicious to Baron Knigge, who in 1784 accused him of being a camouflaged Jesuit spy.

He subsequently left the order amidst scandal. In 1784, following numerous accusations leveled against the Illuminati, the order was officially dissolved by the Elector of Bavaria. Weishaupt lost his chair, moved to the city of Gotha, and published anti-monarchist pamphlets extolling the power of human reason.

The brief existence of the Illuminati coincided with an exceptionally turbulent period in world history. In 1776, the Declaration of Independence was signed, establishing the United States of America. In 1789, a revolution broke out in France, completely changing the history of Europe. These two events played a fundamental role in the development of the Illuminati legend, giving rise to the immense popularity of various conspiracy theories.

The shock of the revolution, its scale, and the enormous social change it triggered almost immediately resulted in the development of various fantastical concepts about the forces behind it all. Meanwhile, shortly after Weishaupt’s dissolution, most of the secret documents of the Bavarian lodge were published — thanks in part to Knigge.

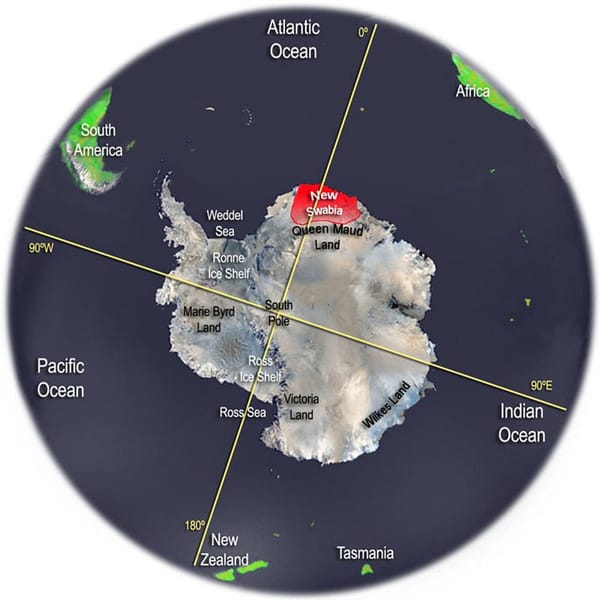

The ideals espoused by the Illuminati — primarily equality, freedom, and republicanism — guided both the signatories of the American Declaration of Independence and the French revolutionaries. Enlivened by the revelation of the Illuminati’s claim to world domination, the imagination of European and American public opinion immediately linked the order’s ideology with groundbreaking historical events. The writings of Weishaupt and his associates quickly penetrated the United States, and a supposed Illuminati symbol appeared on the dollar bill: an eye within a pyramid. The symbol was, of course, an old one, dating back to the Renaissance and having nothing to do with the small Bavarian lodge.

But the idea of secret leaders striving to fundamentally reshape traditional society had already become a dominant theme, engaging even the most serious thinkers and politicians, with George Washington at the forefront.

In the 19th century, the Illuminati legend was revived by Eliphas Lévi, a prominent French occultist, who published his famous “History of Magic” in 1860. In it, he attributed to Weishaupt an interest in the occult and necromancy, the practice of contacting the dead, and traced the Illuminati’s lineage to the Knights Templar and Rosicrucians.

A dozen or so years later, the Illuminati were reestablished by Theodor Reuss, later founder of the magical lodge Ordo Templi Orientis (Order of the Temple of the East), whose most famous member was the scandalous English magician Aleister Crowley, who died in 1947. He was one of the favorite heroes of the 1960s counterculture (his photo appears on the cover of The Beatles’ album “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band”), and is still often — and erroneously — considered a Satanist. Crowley also referred to the Illuminati in his writings — and it is probably thanks to him that they are experiencing a gigantic renaissance today.

Jordan Maxwell, a tireless tracker of conspiracies and secret societies, who for decades has published books and articles exposing Illuminati machinations, has no doubt that the Illuminati plays a fundamental role in human history.

For Maxwell, however, Weishaupt is merely one of the order’s many leaders, more of a figurehead, brought to the forefront primarily to deflect attention from the society’s true leaders, who effectively hide in the shadows. Together with David Icke — a former BBC sports commentator who experienced a profound spiritual enlightenment in 1991 and declared himself the son of God, and subsequently began publishing books devoted primarily to the Illuminati — Maxwell details the Illuminati’s involvement in key historical events.

Their books sell enormously, and their public appearances — organized by devotees almost worldwide — always attract large crowds.

The French Revolution and the signing of the Declaration of Independence, according to them, were, of course, the work of the Illuminati. The secret sect is also behind all wars, governments, banks, and the entertainment industry. It’s difficult to identify any area of public life that the Illuminati don’t control. “Nothing that happens is accidental,” Maxwell likes to say, and David Icke echoes him.

Both agree on another point: The Illuminati are not only cunning conspirators. They are also representatives of a completely alien race: the reptilians, shape-shifting, giant lizards who came to Earth thousands of years ago from the distant constellation of Draco.

Anyone reading this who is feeling guilty should familiarize themselves with a report published in early April of this year by Public Policy Polling, one of the largest American institutions researching Americans’ beliefs and beliefs. According to this report, approximately twelve million US citizens currently believe in a reptilian conspiracy.

David Icke even claims to have a sworn statement from an anonymous woman who describes in detail how members of the Bush, Clinton, Rothschild, and Rockefeller families would assume their true form before her eyes — the classic reptilian, standing five to ten feet tall and resembling a humanoid, scaly green lizard — then kill innocent people and drink their blood with gusto.

With similar self-assurance, Icke also explains that Princess Diana’s death was anything but accidental. The reptilians decided to eliminate her because she had learned their terrifying secret. Fortunately, just before her death, she managed to reveal it to Icke, who now knows with absolute certainty that members of the British royal family are, without exception, members of this repulsive, lizard tribe.

At night they transform into enormous reptiles, drink human blood, and engage in other filthy pastimes, while during the day they take on the benevolent forms of Queen Elizabeth or Prince Charles.

JFK’s assassination is also linked to a reptilian conspiracy. Opinions are divided on this point — it’s unclear what motivated Kennedy’s execution (some conspiracy theorists argue that he, too, was an Illuminati, albeit a rebellious one).

However, his murder was undoubtedly ritualistic in nature, in which a certain Umbrella Man played an unclear but certainly decisive role

In photographs documenting the Dallas assassination, a mysterious figure with an umbrella appears (remember, it was a clear and sunny day), who, as the president’s limousine drives down Main Street, for unknown reasons unfolds the umbrella just seconds before the fatal shot. Whether this was a secret signal to the assassins or — as some claim — a magical act that was the actual cause of JFK’s death, we will likely never know. Suffice it to say that the Umbrella Man — who was identified thirteen years later and claimed that the umbrella was a form of political protest against Kennedy’s policies, but, as you might guess, Maxwell and Icke believe it was about something completely different — was certainly in the service of the Illuminati.

So why, it’s worth finally asking, has this camouflaged society become a favorite subject of Hollywood productions? The Lara Croft film series starring Angelina Jolie, Dan Brown’s books and the films based on them, and “National Treasure” starring Nicolas Cage and Diane Kruger — these are just a few recent films in which the Illuminati are portrayed as a ruthless group of influential conspirators, either already ruling the world or effectively striving for such power.

Well, the Illuminati — as I mentioned earlier — hold the American film industry in their grip, and the most perfect way to camouflage their existence is to make themselves heroes of popular fiction. This relegates the topic to the frivolous realm of pop culture, and the real conspirators can freely prey on a public befuddled by the pulp of film.

Anyone who breaks away from this Hollywood conspiracy, however, will face severe punishment. So how is it that Jordan Maxwell and David Icke, who openly expose the conspiracy of predatory lizards, are still in good health? The answer is incredibly simple.

Eliminating anyone who openly describes the Illuminati would be an unacceptable act of self-exposure on their part. This is undoubtedly comforting for any author — including this writer — who tries to educate readers about this all-powerful, terrifying society.